Preferential Imports of High Elasticity Systems: Why Chile's Profits Don't Reach East Asia and Effective Policy Design.

Input

Modified

This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The EduTimes editorial team, in collaboration with SIAI’s Global School of Business (GSB). While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

The most revealing number is not a grade or a place in university rankings. That's 29.2 trillion Korean won (Roughly USD 21 billion) — the record spending of Korean households on private education in 2024 — at a time when the student population is shrinking. Combine this with a second figure: 47.6% of children under six already attend tutoring, with a quarter starting before two. These two facts say more about the policy field than any slogan about "meritocracy" or "opportunity." In systems where the family response to motivation is hyperelastic and begins at a very young age, even well-intentioned preferential admission arrangements can be arbitrated on a large scale. By contrast, in Chile, where an in-school scheme for top disadvantaged high school students increased access to selective universities without causing massive "manipulation," the benefits were measurable — albeit with margin limits. The position of this article is straightforward: privileged admissions can work where behavioral responses are restrained and tertiary education remains partial; fail, or boomerang, in environments like Japan, Korea or China, where families quickly readjust strategies around each new rule. The question is not whether to widen the opportunities, but how to design them so that they cannot be bypassed.

Framing the question: from access to incentives

The public debate on preferential admissions usually asks whether disadvantaged students' access to academic criteria without undue harm is increased. This framework ignores the deeper variable that judges success: the elasticity of pre-university behavior towards the admission rule itself. In low-flexibility environments — where few pursue tertiary education, where private tutoring support is limited, and where school placement is difficult to manipulate — schemes that reward top performers in understaffed schools can produce 'absolute mobility', which means a significant increase in the number of students from disadvantaged backgrounds who successfully enter tertiary education, with 'tolerable side effects', meaning the negative consequences of the policy are manageable. In high-flexibility environments — where almost everyone is aiming for university, where households mobilize money and time years in advance, and where school placement or housing is strategically remodeled — the same rules trigger 'gaming,' poor distribution, and late dropouts. The Chilean scheme of 'top x% within disadvantaged schools' has increased access and subsequent earnings on average. The Korean culture of early, intensive, and adaptive preparation would turn the same rule into a strategic transfer match. Political debate, therefore, is not 'yes/no', but 'planning under behavioral constraints'.

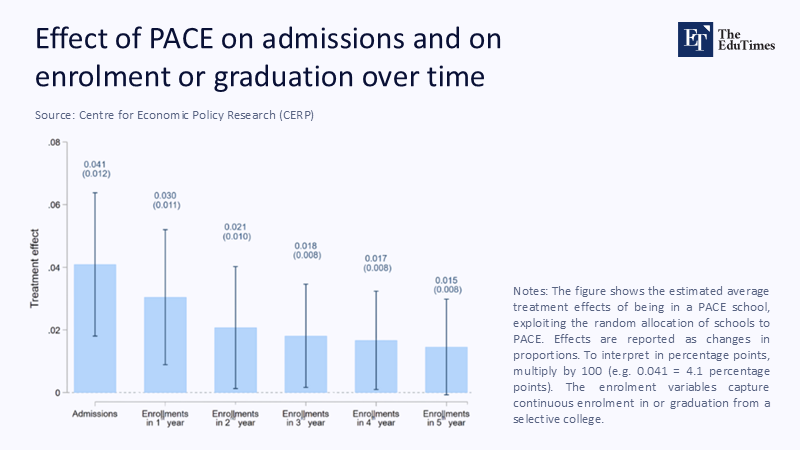

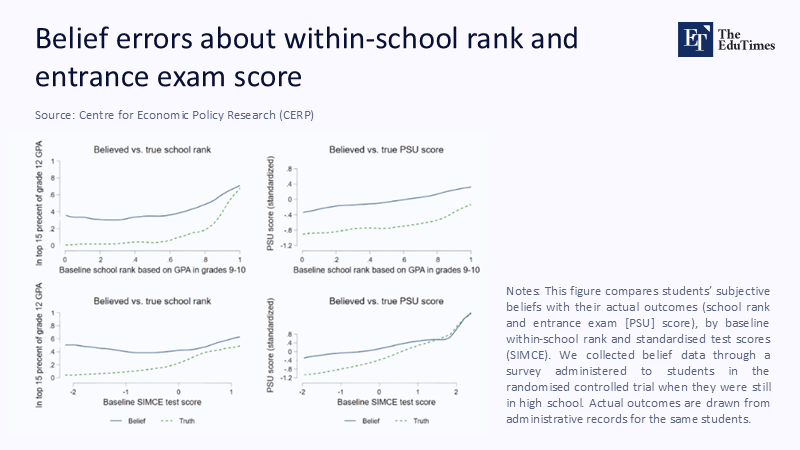

Why the Chilean model moves the index — and its potential

Chile offers unambiguous documentation. A national program that guaranteed a place in selective institutions for the top 15% of disadvantaged high school graduates increased first-year enrollment and, for the average beneficiary, improved future earnings, mainly because students were admitted to more selective programs. However, the same data illuminates hard limits. Marginally eligible students showed higher dropout risks and weaker returns later on, consistent with academic readiness "mismatch" when the program is demanding. A key finding is that beliefs and motivation count. Some students reduced effort in high school by predicting the preferential pathway, while simple, targeted information improved choices without the side effects of generalized relaxation. The conclusion is not that preferences "work" or "don't work", but that in contexts like Chile's — medium-range tutoring, limited ability to "buy" school, part-time tertiary education — targeted preferences plus information can increase mobility, as long as there are railings that maintain motivation and academic matchmaking. This mixture is complex to reproduce when home adaptation is faster and stronger.

The reality of East Asia: when families move faster than politics

East Asian systems change the equation. The tertiary participation rate in Korea is essentially universal by international standards, and the preparation culture is both early and intensive. The statistical office records new records of expenditure on private education in 2023 and 2024; International reports confirm that almost half of pre-kindergarten children attend tutoring centers, especially in the privileged neighborhoods of Seoul. The participation of school-age children in private aid is approaching saturation, while analyses by the government and the OECD link the 'arms race' with broader social costs. In China, the combination of provincial quotas and differences in exams has historically produced 'gaokao migration,' with families changing hukou or school to optimize the odds — an archetype of high political responsiveness. In this landscape, a rule that 'locks' into a 'disadvantaged school', which refers to a school with a high proportion of students from low-income or underprivileged backgrounds, is tantamount to an invitation to strategic transfers, changes of direction, or regular school re-matching. We are not talking about hypothetical risks; They stem from the observed willingness of families to spend, move, and plan years in advance to extract even marginal advantages.

What the Korean withdrawal signals: the "lowering of the bar" does not level the field

An enlightening counterweight is the Korean postgraduate experiment that opened the door wide to candidates from across the spectrum of institutions, including those whose internal indicators predicted they would struggle. The short-term gain in equality was undeniable — doors that had hitherto been closed were opened — but the medium-term outcome was harsh: over 60 percent left before completing half of the courses, and less than one in five finished with a thesis. The evaluation of the program itself attributed the failure to a discrepancy between training optimized for the reproduction of test standards and the requirements of an open-type, problem-centered study, with a few notable exceptions from "non-branded" institutions distinguished by strong innate ability. Other Korean data shows increased dropout rates in STEM master's degrees for international students compared to domestic students. None of this "proves" that graduates of disadvantaged schools cannot succeed; It shows that the introduction of itself, in a system optimized for testing and early specialization, can widen the discrepancy if it is not accompanied by serious preparation and support. In short, horizontal preferences without scaffolding build failure.

Designing for Asia: the imperative of equality without loopholes

If the problem is flexibility, the solution is to reduce the policy surface that households can exploit and transfer resources from "positioning" to preparation. First principle: transition from school labels to place-bound local disadvantage indicators, difficult to falsify, combining long-term residence, neighborhood deprivation, and cross-income with consistency checks over time. Second: the privileged admission must be conditional on pre-registration and bound to acquired proficiency – offer of a place conditional on the successful completion of standardized bridging modules that close the fundamental gaps of the targeted school. Third: breaking the single high limit in tiers by randomizing bonds within tiers; Randomization on the sidelines cancels out surgical "gaming" targeting without sacrificing value signals. Fourth: active audit and feedback; Import services publish "anomaly flags" (sudden bursts of transfers in eligibility zones, unlikely changes of residence) and dynamically regulate the boundaries. Each element channels the family effort towards the accumulation of human capital instead of strategic repositioning. In East Asia, this reorientation is the main prize.

Preparation as a binding constraint: bridges that endure

Preferential admissions fail when they "admit" students to demanding programs without time to acquire the knowledge infrastructure that was not rewarded in school. Data on university bridges — though not homogeneous — show substantial gains in scoring and retention when the intervention teaches absolute prerequisites over a horizon of weeks and months, not days. At the same time, studies on very short pre-PhD "starts" warn against making excessive promises; Lasting benefits require duration, credits, and alignment with the final evaluation. The practical conclusion for Asia: preferential offers to be "linked" with credit, semester-long master's paths, co-taught by the same host schools, which end up in portals-evaluations that become a condition of full enrollment. This protects the criteria, concentrates investment in skills, and enables a dignified exit with a recognisable certificate – not a stigma – when the match does not prove to be correct. The U.S. debate over the reintroduction of standardized testing also points to a hybrid: where schools are "unknown," calibrated tests can protect high-achievers from disadvantaged environments, provided they are a signal among more.

What do teachers, administrations, and policymakers do now?

Teachers should redesign the first year of study to recognize heterogeneous readiness and "load" early diagnostic teaching, reducing the reliance on the "sink or swim" that punishes exactly the students that equality policies bring in. Administrations should massively pilot conditional offers, treating bridging programs as an integral phase of the degree, and publish transparent indicators: acquisition rates, credit accumulation, and two-year stay per admission route. Policymakers shift resources from blunt redeployments to targeted, early capacity building – particularly in mathematical thinking, writing, and evidence-based argumentation – starting in the last years of secondary school. They should also introduce disincentives to manipulation, tied to location markers and long-term residency certification, avoiding public signals that create abrupt "cliffs" of incentives. Finally, all actors should treat students' beliefs as policy levers: information campaigns that accurately capture the effort required per sector and the yields of the "master" can shift the study to the substance at a much lower cost than constantly cutting and sewing admission lines.

Dealing with objections — with evidence

One objection says that preferential imports necessarily "lower" the level and therefore harm those who are supposed to help. The Chilean archive shows the opposite on average when preferences are targeted and accompanied by reliable information; Failures accumulate in marginally eligible ones where the readiness gap is greater — a design problem, not a necessity. A second objection argues that Asia's intensive prep culture makes strong preferences imperative to "compensate" for tuition inequality. But if the policy surface is manipulable, we subsidize "gaming", not learning; The Korean private spending struggle and the "gaokao migration" to China show how quickly families are reacting—third objection: "test-optional" or "holistic" assessments already solve the problem. Newer U.S. figures are mixed: some institutions report gains in diversity and inclusion, others find that optionality may inadvertently reduce visibility for high-achievers from low incomes, prompting top universities to reinstate exams as part — not everything — of a holistic crisis. The right lesson is not the worship of the test, but the plurality of signals and the scaffolding of "master".

We plan for motivation, not intentions

Let's go back to those two figures: 29.2 trillion. Won and 47.6% of those under the age of six in tutoring schools. They describe an ecosystem in which families will reorganize budgets, housing, and time in response to every admission rule that offers an advantage, no matter how small. In such systems, the mechanical transfer of the Chilean rule based on ranking within "disadvantaged" schools is not progress realism; It is political naivety. The way forward is to narrow the arbitrage surface and widen the preparation pipeline: multi-year site markers that cost to falsify; coupling each offer with substantive, credit gain; randomization on the sidelines to "break" surgical targeting; and publishing evidence that beliefs can shift toward effort rather than loopholes. Where behavior is less elastic, preferences can continue to elevate mobility. Where it's hyperelastic, the choice is sharper: we design for motivation, not intentions — otherwise we'll see the promise of equality again turn into an arms race that parents win and students lose.

The original article was authored by Michela Tincani, an Associate Professor at University College London (UCL), along with two co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "When beliefs shape policy outcomes: Lessons from preferential college admissions in Chile," was published by CEPR on VoxEU. For more information about SIAI’s Gordon School of Business and Artificial Intelligence, please visit https://gsb.siai.org.

References

Bloomberg. (March 13, 2024). Spending on private education hits another record in South Korea. Reference to Statistics Korea data.

British Council. (24 June 2025). Slight dip in Gaokao candidates after 2024's record high.

Carlana, M., Miglino, E., & Tincani, M. (2024). How far can inclusion go? The long-term impacts of preferential college admissions (CEPR Discussion Paper DP19128). Centre for Economic Policy Research.

Carlana, M., Miglino, E., & Tincani, M. (2024). How far can inclusion go? The long-term impacts of preferential college admissions (conference version). World Bank.

College Board. (June 2025). New evidence on the effect of changes in testing policies (ARC Research Brief).

Financial Times. (17 March2025). South Korea's academic race pushes half of under-6s into "cram" schools.

Grossman, J., Tomkins, S., Page, L., & Goel, S. (2024). The disparate impacts of college admissions policies on Asian American applicants. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 4449.

Gordon Institute of Artificial Intelligence. (March 19, 2025, updated June 9). Why SIAI failed 80% of Asian students: A cultural, not genetic, explanation. giai.org.

Korea JoongAng Daily. (7 October 2024). High dropout rates persist for many international graduate students.

Korea Labor Institute. (31 March 2025). Panel Brief: Private education participation trends.

OECD. (2023). PISA 2022 results (Volume I): The state of learning and equity in education. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/53f23881-en

OECD. (July 3, 2024). OECD economic surveys: Korea 2024. OECD Publishing.

Reuters. (February 22, 2024). Yale reinstates standardized test requirement, citing benefits for diverse high-achievers.

Statistics Korea. (13 March 2025). Private Education Expenditures Survey of Elementary, Middle, and High School Students in 2024.

Tincani, M. M., Kosse, F., & Miglino, E. (2025). Beliefs and the incentive effects of preferential college admissions: Evidence from an experiment and a structural model (working paper). University College London.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2025). Gross enrolment ratio in tertiary education (dataset, 1970–2025). Our World in Data (adapted).

University of California, Davis (reported by Davis Vanguard). (August 2025). Study finds test-optional policies can boost diversity, with caveats.

Washington Post. (10 June 2025). Cram schools for kindergartners are the latest in South Korean college prep.

World Bank. (2025). School enrollment, tertiary (% gross): Chile; Korea, Rep. (UIS series).